This outline frees people from prison.

/It's the most persuasive way to organize any persuasion, from a job interview to a documentary film.

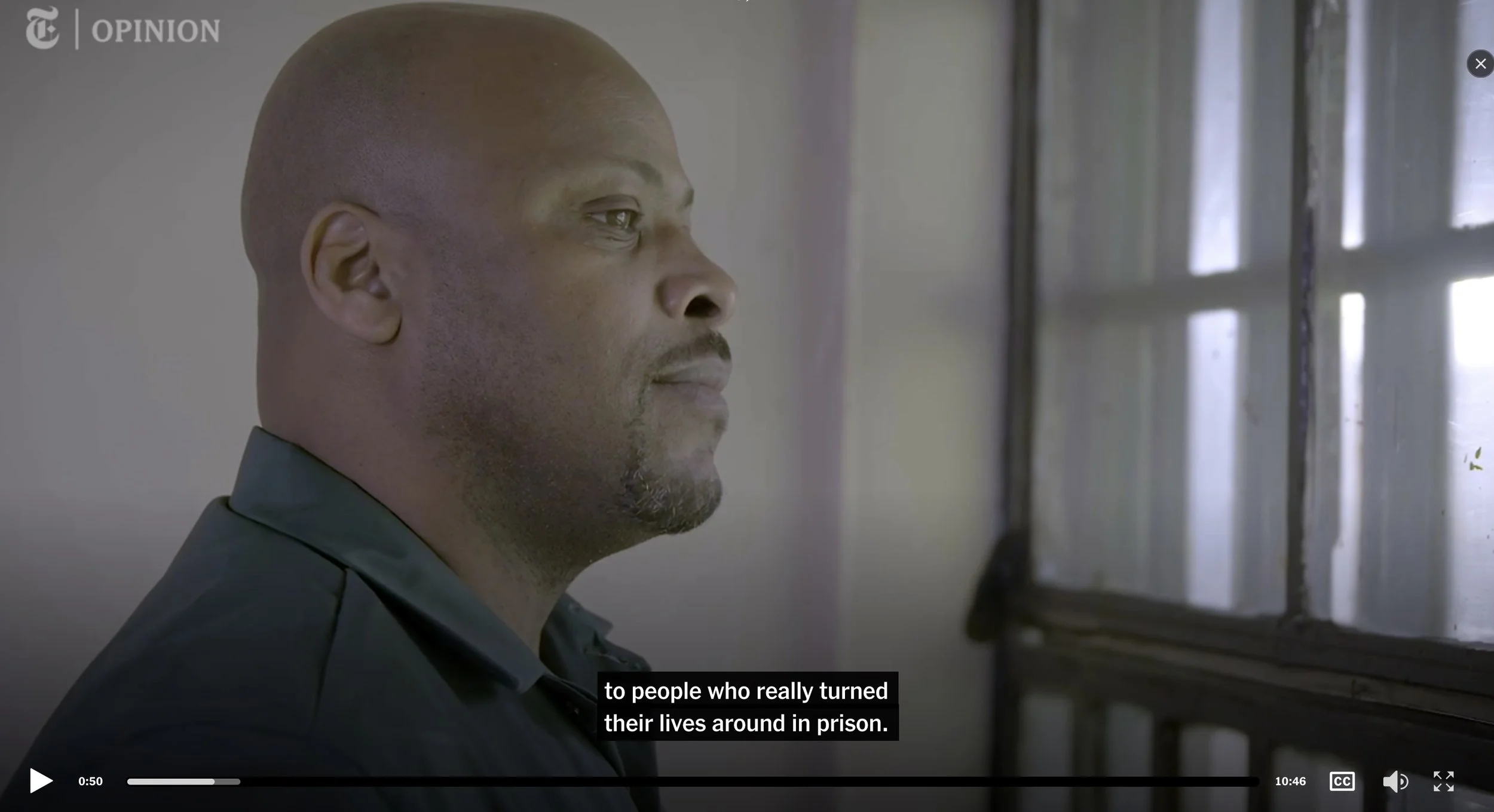

The filmmaker Matt Nadel crafts short documentaries of New York State prisoners. His purpose: to get the governor to grant clemency. You’ll find the story here (gift link).

Nadel’s audience consists of one person: the governor. See his NYT doc here.

Nadel is a naturally skillful rhetor; his films occasionally succeed in springing convicts from prison, despite the increasing odds. Ever since the tough-on-crime era of the 1980s, governors have been afraid to release prisoners; so Nadel has to perform a powerful bit of persuasion.

He does this in part by following a classic Ciceronian outline: Ethos, then Logos, then Pathos, then moral.

Ethos

The films begin with the prisoner’s life story, beginning with a invariably horrible childhood. This turns the convict from a “predator” or “criminal” or “monster” into a pitiable human. The ethos is the projected character, likeable and trustworthy.

Logos

The prisoner speaks of his or her crime in plain, honest terms. No euphemism or passive voice. Cicero would say this is the narratio, the story part of logos, where the speakers offers the facts.

Pathos

Nadel’s subjects express deep regret. You can see the tears. Pathos, or the tactical use of emotion, attempts to sync with the audience, sharing the mood.

Moral

The peroration of any great oration offers the “why”—the meaning behind the message. That’s what John F. Kennedy did in his famous moonshot speech.

We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.

In Matt Nadel’s prison films, the prisoners provide the peroration by redefining their ethos: “I’m a different person today.” That’s the moral to the story, the why. It refames the character from someone who deserves prison to an evolved soul whose crime is a painful memory.

The same outline can help with any persuasion of your own. (1) Establish trust and likeability with a well-defined ethos. (2) Tell your story in a credible way. (3) Build to an emotional climax. (4) And don’t miss the moral, preferably through a well-crafted period.

But first, see Nadel’s film for the New York Times. While you’re watching it, note the outline he uses. Look familiar? Whose ethos is Nadel conveying?